10. Privacy

The traditional banking model achieves a level of privacy by

limiting access to information to the parties involved and the

trusted third party. The necessity to announce all transactions

publicly precludes this method, but privacy can still be

maintained by breaking the flow of information in another place:

by keeping public keys anonymous. The public can see that someone

is sending an amount to someone else, but without information

linking the transaction to anyone. This is similar to the level of

information released by stock exchanges, where the time and size

of individual trades, the "tape", is made public, but without

telling who the parties were.

As an additional firewall, a new key pair should be used for each

transaction to keep them from being linked to a common owner. Some

linking is still unavoidable with multi-input transactions, which

necessarily reveal that their inputs were owned by the same owner.

The risk is that if the owner of a key is revealed, linking could

reveal other transactions that belonged to the same owner.

11. Calculations

We consider the scenario of an attacker trying to generate an

alternate chain faster than the honest chain. Even if this is

accomplished, it does not throw the system open to arbitrary

changes, such as creating value out of thin air or taking money

that never belonged to the attacker. Nodes are not going to accept

an invalid transaction as payment, and honest nodes will never

accept a block containing them. An attacker can only try to change

one of his own transactions to take back money he recently spent.

The race between the honest chain and an attacker chain can be

characterized as a Binomial Random Walk. The success event is the

honest chain being extended by one block, increasing its lead by

+1, and the failure event is the attacker's chain being extended

by one block, reducing the gap by -1.

The probability of an attacker catching up from a given deficit is

analogous to a Gambler's Ruin problem. Suppose a gambler with

unlimited credit starts at a deficit and plays potentially an

infinite number of trials to try to reach breakeven. We can

calculate the probability he ever reaches breakeven, or that an

attacker ever catches up with the honest chain, as follows [8]:

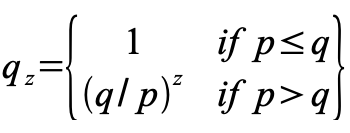

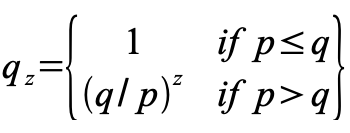

p = probability an honest node finds the next block

q = probability the attacker finds the next block

q z = probability the attacker will ever catch up from z blocks behind

q = probability the attacker finds the next block

q z = probability the attacker will ever catch up from z blocks behind